Public Land on the U.S.-Mexico Border

Picture the public land on U.S.-Mexico border. Perhaps you see a distinct line slicing across the map or a fence enforced by the Border Patrol cutting through a desert wilderness. Or maybe you imagine a port of entry where sister cities straddle the international boundary.

While hardly incorrect, such images can over-simplify the complicated reality of the border as well as the management of the lands surrounding it.

The long history of land management along the border reveals that many kinds of U.S. public lands neighbor the boundary. Americans have valued them for military purposes, recreation, environmental preservation, and economic development, among other purposes.

Public Land Conservation and National Security

Land stewardship and national security need not be incompatible. By understanding the many the reasons why Americans have set aside these lands in the past, we can promote historic conservation goals as well as interagency cooperation between border enforcement and land management to avoid sacrificing the region’s cultural and natural histories to the maw of national security.

Given today’s heated political rhetoric regarding the border, an understanding of the many values people have placed on the borderlands is more necessary than ever. History shows that a variety of beneficial uses have long coexisted in the borderlands. Today’s new concerns about immigration, drugs, and security should be integrated into this nexus of uses.

A Long History behind Public Land on the Border

Prior to American and Mexican control, much of the region that would come to be known as the borderlands had been inhabited for thousands of years by various Native American peoples such as the Tohono O’odham, the Cocopah, and many others.[1] Following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the U.S.-Mexico border cut right through these and other tribal homelands. The governments of both countries relegated the once wide-ranging tribes to much smaller pieces of land along the border, where many of these groups still reside.[2] These tribes value the land along the border for the historical and cultural connections they have in this region.

As the U.S. and Mexico began colonizing the region, private land users increasingly valued the desert for economic gain. Mineral prospectors staked claims. Homesteaders farmed. And ranchers grazed livestock. In fact, private land-owners actually built the first fences along the border in order to differentiate ranch and farm lands of the property owners who had grown tired of horse and cattle rustling, and who were also looking to stop the spread of livestock diseases.[3]

By 1907 the border was defined even more clearly when President Theodore Roosevelt, valuing national soveriegnty, issued a proclamation reserving a sixty-foot wide swath of land along the borders of California, Arizona, and New Mexico for federal use to combat opium smuggling and to enforce immigration policies.[4] Shortly after, in response to incursions during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), the federal government increased its presence along the border to shore up national security.

Developing a Conservation Ethic

It was also during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that Americans began increasingly to value the idea of environmental conservation. Much of the land that the border ran through was found to be a fragile ecosystem with flora and fauna not found anywhere else in the United States.[5] In order to protect these areas for the enjoyment of future generations, many people began to call for greater federal protections. Over the following decades, the

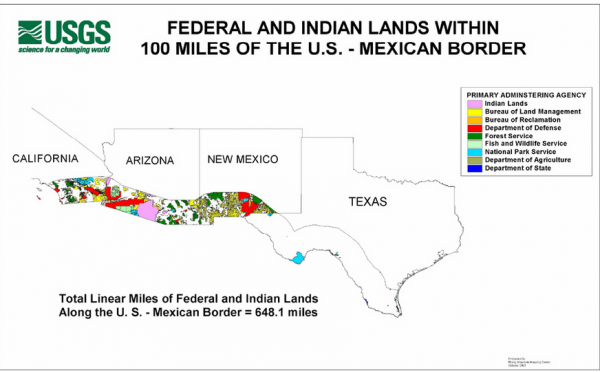

federal government reserved much of the land along the western half of the border to protect various species and environments and to promote recreation. These lands are managed by a variety of agencies including the National Park Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service. They include treasures such as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona, Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge in southern Texas, and Border Field State Park marking the border on the Pacific Coast in California.

A Complicated Landscape

Reserved lands are not limited to environmental conservation, however, as there are also countless water management districts created to allocate and maintain the flows of rivers that cross the international border,[6] as well as large tracts of land set aside for the Department of Defense such as the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, a large section of land in south-west Arizona designated during World War Two, and still in use today, to train Air Force Pilots in combat maneuvers.[7] The Bureau of Reclamation manages water. The Forest Service manages timber, watersheds, and recreation. The Bureau of Land Management promotes grazing, mining, and recreation. All told, public lands dedicated to many valuable uses constitute roughly 40% of the border.[8]

Conclusion

Clearly, the U.S.-Mexican border and management of public land are more complex than the enforcement of a simple line cutting through the desert. The borderlands consist of a vast network of federal and state agencies, Native American tribes, and private property owners who each manage their respective lands toward desirable public and private ends. Although these uses have sometimes clashed in the past, and will continue to do so in the future, understanding this history reminds us that we value the border region today for many things. When it comes to border policy, we should take all of these values into account and not sacrifice them to walls.

By Daniel Gilbert

CSU History and Political Science major

Class of 2018

References

Gurbacki, Karrie A. “Migration of Responsibility: The Trust Doctrine and the Tohono O’odham Nation.” Mexican Law Review 6, no. 2 (January-June 2014): 273-96. Accessed April 5, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1870-0578(16)30015-4.

Sharp, Christopher and Randy Gimblett. “Assessing Border-Related Human Impacts at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.” in Conservation of Shared Environments, edited by Laura Lopez-Hoffman et al., 226-40. Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2009.

St. John, Rachel. Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2011.

US Congressional Research Service. U.S.-Mexican Water Sharing: Background and Recent Developments, by Nicole T. Carter, Stephen P. Mulligan, and Clare Ribando Seelke, CRS 7-5700, March 2017.

US Government Accountability Office. Southwest Border: Border Patrol Operations on Federal Lands, statement of Anu K. Mittal, Director of Natural Resources and Environment, GAO-11-573T. Washington, D.C., April 15, 2011.

Western Regional Partnership Public Affairs Office. “Barry M. Goldwater Range.” Military Asset List 2015. Arizona: 2015. (Accessed on May 1, 2018). http://www.luke.af.mil/Portals/58/Documents/Barry_M_Goldwater_Range_East_MAL.pdf?ver=2016-03-02-150925-077.

Additional Information

Ganster, Paul and David E. Lorey. The U.S.-Mexican Border Today: Conflict and Cooperation in Historical Perspective. 3rd ed. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016.

Smith, Peter H. and Andrew Selee eds. Mexico and the United States: The Politics of Partnership. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, INC., 2013.

[1] Karrie A. Gurbacki, “Migration of Responsibility: The Trust Doctrine and the Tohono O’odham Nation,” Mexican Law Review 6, no. 2 (January-June 2014): 277.

[2] 55.

[3] Ibid, 73-9.

[4] Ibid, 96.

[5] Christopher Sharp and Randy Gimblett, “Assessing Border-Related Human Impacts at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument,” in Conservation of Shared Environments, edited by Laura Lopez-Hoffman, et al. (Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2009) 228.

[6] US Congressional Research Service, U.S.-Mexican Water Sharing: Background and Recent Developments, by Nicole T. Carter, Stephen P. Mulligan, and Clare Ribando Seelke, CRS 7-5700, March 2017.

[7] Western Regional Partnership, Public Affairs Office, “Barry M. Goldwater Range,” Military Asset List 2015, (Arizona: 2015) accessed on May 1, 2018. http://www.luke.af.mil/Portals/58/Documents/Barry_M_Goldwater_Range_East_MAL.pdf?ver=2016-03-02-150925-077.

[8] US Government Accountability Office, Southwest Border: Border Patrol Operations on Federal Lands, Statement of Anu K. Mittal, Director of Natural Resources and Environment, GAO-11-573T (Washington, D.C., April 15, 2011) 1-2.