In 2017 and 2018, headlines reading, “Protect our Public Lands,” have become a common sight. The Trump Administration’s goal to increase domestic energy production in America has resulted in renewed pressures to extract natural resources on public lands. The case of Dinosaur National Monument in particular illustrates the need to keep fighting the same battles over the same land, being a product of a lack of historical understanding.

Background

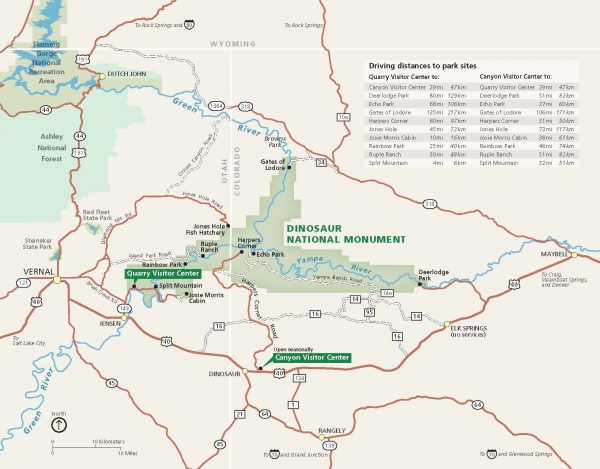

Dinosaur National Monument demonstrates this controversy through the story of Echo Park; a picturesque valley that would possibly have been buried underneath several hundred feet of water. Dinosaur National Monument has been a piece of America’s history for centuries being proclaimed by President Woodrow Wilson as a national monument in 1915 to protect a cliff of dinosaur fossils. Surrounded by twisting canyons and the site of multiple crossing rivers, Dinosaur National Monument inhabits parts of Utah and Colorado showcasing scenic sandstone gorges enjoyed by millions who have passed through these public lands. The Bureau of Reclamation issued a plan in 1946 for the construction of several large dams among the upper Colorado River and some of its tributaries called the Colorado Basin Storage Project that would have deconstructed these public lands.[4]

Controversy

Cultural shifts in American society following World War II led many Americans to celebrate the nation’s victory by taking to the highways and traveling to places they could now afford to visit: National Parks.This travel boom introduced new understandings of the environment that prioritized protecting America’s unique landscapes for future generations. Many conservation groups such as the Wilderness Society, the Sierra Club, and the National Parks Association, recognized the destructive impact that the Echo Park Dam would have on a treasured National Monument and its landscape. They also feared the precedent a dam would set for preservation in other national parks. Organizations entered the national spotlight and gathered public support as they protested the construction of the Echo Park Dam. For these organizations and regular Americans, resisting the Echo Park Dam represented a shared set of values and priorities: stewardship of wild places, the importance of having experiences in nature, and the preservation of those places for future generations. Over the next few years conservationists publicized the Echo Park controversy by challenging the engineering of the dam and producing films and articles that showcased the beauty of the park. They also persuaded thousands of constituents to urge their congressional representatives to oppose the dam. The successful campaign captivated Americans, reaffirmed the nation’s commitment to the national parks system, and proved Dinosaur was an area worth preserving.

By 1955 upper basin Denver lawmakers had come to a compromise with conservationists: they would leave Echo Park undeveloped, if they could build instead in Glen Canyon, outside National Park System land. Conservationist groups agreed to the tradeoff but later regretted their decision, adding to the bitterness between conservation groups and the Bureau.In the wake of all the controversy, President Eisenhower signed a bill that “prohibited dams in any area of the national park system along the Colorado River,” and conservationists rejoiced that they had set a new precedent for public lands. The historic event became a milestone in American conservation history and the American environmental movement, but the fight has not ended here.

What’s happening in Dino today?

Fast forward to 2017. Utah’s governor Gary Herbert wrote to federal officials asking them to defer a planned oil and gas lease sales near Dinosaur National Monument. Today, the Bureau of Land Management has conducted oil and gas lease sales which include areas of land alarmingly close to Dinosaur National Monument and other NPS land, including national parks. The Trump administration is attempting to intensify domestic energy production, a policy it has branded “energy dominance,” by increasing gas, oil and coal extraction on federal lands; a policy that increasingly threatens protected public lands around the country. The National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Utah, conservation organizations, and local ranchers have all shown their concern about the possible development of land adjacent to Dinosaur.

Scott Chew, the state GOP Rep. who lives nearby Dinosaur also voiced his anxieties on the development stating, “We like to see the revenue generated by the extractive industry, but on two of the parcels, right next to the monument, there is some concern. I know the residents are eager to get back to work and want to protect the monument, too.”

Three of the sites nearly overlap the park’s entrance as well as the Green River and can be seen from the visitor center and the Carnegie Fossil Quarry. The development is not only concerning for conservationists but also for the local economy that surrounds tourism. National Parks Conservation Association officials Cory MacNulty and Jerry Otero wrote in comments to the BLM that visitor experience in the monument will be negatively impacted by increasing nighttime sky glow, impairing the scenic views, increasing heavy equipment traffic on the primary entrance road into the park, elevating ambient noise levels and diminishing water and air quality.

Why does this matter?

The value of a historical perspective can always shed light on a present public issue. As shown in the case of Dinosaur, the same exact area of land that thought it had set an environmental precedent is under the same controversy as it was decades ago. Dinosaur is not the only land in the Parks system facing this issue today; up to 40 other parcels of land within and adjacent to park boundaries including places like Theodore Roosevelt, Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Everglades, and Cuyhoga Valley are currently facing debate over resource extraction. In fact, energy development is not the only battle National Parks are currently facing. In December of 2017 President Trump’s review of certain monuments left Grand Staircase- Escalante National Monument and Bears Ears reduced in size and in question on the issue of resource extraction. If the actors who have a current stake in the future of our National Parks had more historical awareness on the subject, maybe Dinosaur National Monument could have set a lasting conservation precedent for future generations as it had originally thought.

-Alexandria Kearney, PLHC Intern

[1] “Six Interior Infrastructure Projects that Benefit the Public,” The White House. June 7, 2017. https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/6-interior-infrastructure-projects-benefit-public/

[2] Dylan Ball and Daniel Kaneb, “Dinosaur National Monument,” Colorado Encyclopedia , http://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/dinosaur-national-monument

[3] “Annual Park Recreation Visitation,” National Park Service. 2017. https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20Recr ation%20Visitation%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=DINO.

[4] Mark Harvey, “Battle for Dinosaur,” in A Symbol of Wilderness: Echo Park and the American Conservation Movement.

[5] Harvey, “Battle for Dinosaur.”

[6] Harvey, “Battle for Dinosaur.”

[7] Ball and Kaneb, “Dinosaur National Monument.”

[8] Harvey, Mark. “Battle for Dinosaur,” in A Symbol of Wilderness: Echo Park and the American Conservation Movement.

[9] Ball and Kaneb, “Dinosaur National Monument.”

[10] Harvey, “Battle for Dinosaur.”

[11] Harvey, Mark. “Battle for Dinosaur.”

[12] Ball and Kaneb, “Dinosaur National Monument.”

[13]Mark Jason, “Oil Drilling: Coming to a National Park or Monument Near You?” Sierra. September 19. 2017. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/oil-drilling-coming-national-park-or-monument-near-you

[14] “Six Interior Infrastructure Projects that Benefit the Public,” The White House.

[15] Maffly, Brian “Herbert asking BLM to ‘re-evaluate’ oil and gas leasing near Dinosaur National Monument,” The Salt Lake Tribune. July 30, 2017. https://www.sltrib.com/news/environment/2017/07/30/herbert-asking-blm-to-re-evaluate-oil-and-gas-leasing-near-dinosaur-national-monument/

[16] Maffly, “Herbert asking BLM to ‘re-evaluate’ oil and gas leasing near Dinosaur National Monument,” The Salt Lake Tribune.

[17] Maffly, “Herbert asking BLM to ‘re-evaluate’ oil and gas leasing near Dinosaur National Monument.”

[18] “Oil and Parks Don’t Mix,” National Parks Conservation Association. 2018. https://www.npca.org/advocacy/73-oil-and-parks-don-t-mix

[19] Lund, Nicholas. “The Facts on Oil and Gas Drilling in National Parks,” National Parks Conservation Association. March 29, 2017. https://www.npca.org/articles/1471-the-facts-on-oil-and-gas-drilling-in-national-parks