The following is a repost from History Colorado’s Weekly Digest that appeared in the August 28th edition under the title “Health, Recreation, Education, and Uplift: Lincoln Hills and Black Recreation in the Colorado Mountains.” To visit the original post, visit the History Colorado website.

Lincoln Hills

When temperatures soared in cramped, noisy cities, Colorado’s higher elevations promised chilly nights and mild days spent fishing, camping, and hiking under shady pine trees. Unlike their white counterparts, however, African Americans could not head just anywhere in the mountains. Just outside of Denver, Lincoln Hills, a vacationing community developed for Black people, represented both an escape from the city and from segregation. This escapism had its limits, though, as racism was not confined to Colorado’s urban spaces. African Americans considered outdoor recreation in Colorado’s mountains an essential part of wellbeing and an important marker of respectability that was intimately linked to social movements that sought racial equality. Due to the ways that racism shaped outdoor recreation on public land and the communities that were the gateways to public land, Black people created Black spaces on private land on which to recreate as a solution to a problem of access to natural spaces and as a politically meaningful statement that complemented social activism within their communities. Lincoln Hills was one of those places.

Denver’s Racial Landscape

Much like Colorado’s outdoor spaces, Denver was segregated more by custom than law. Immediately post-Civil War, small numbers of Black people migrated West, finding opportunities for social mobility and more racial tolerance than in the South, Midwest and Far West. They also enjoyed better access to education and achieved higher literacy rates than Black people elsewhere in the country at the time. Black Denverites made their homes in the Five Points and Whittier neighborhoods north of downtown, fostering a politically engaged and tight-knit community that fostered Black organizations and businesses. In the late nineteenth century, Black people did face racism and discrimination in the West, but the most vehement racial antipathy fell on immigrants from China and Japan.[1] However, that window of relative tolerance at the century’s close was fleeting.

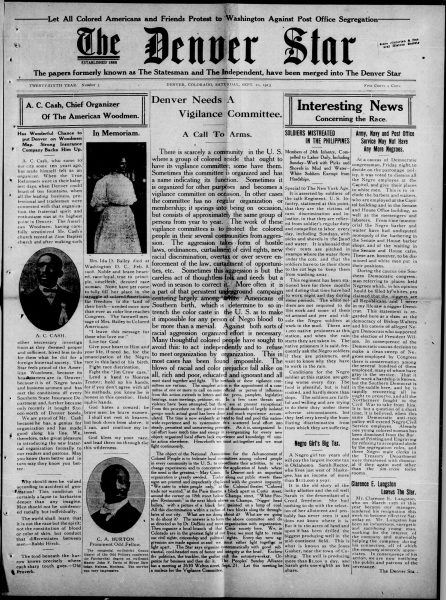

Black Denverites made their homes in the Five Points and Whittier neighborhoods north of downtown, fostering a politically engaged and tight-knit community that incubated Black social and political organizations, as well as businesses. Five Points was home to Black YMCA and YWCA chapters, Black churches, and Black owned newspapers gave voice to the community’s identity and political aims. As early as 1913, The Denver Star called for “a vigilance committee” to combat “hostile laws, ordinances, curtailment of civil rights, new racial discrimination, over tax or over severe enforcement of the law, curtailment of opportunities, etc.”[2] Neighborhood residents formed the Denver chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1915.[3] A year later, the Black community organized to successfully block a plan to legalize residential segregation in the city.[4]

By the 1930s, Denver’s Black community was stable, with 38% of people living in homes they owned. While many notable Black individuals found success in Denver, the majority of African Americans remained employed in service occupations and the Black middle class was economically vulnerable.[5] During roughly the same period, Anti-Black racism in Denver deepened with the founding of the local Ku Klux Klan chapter in 1921.[6] The Klan intimidated and vilified Black people (as well as Jews and Catholics) and backed its claim to political power with threatened and actual violence. The Klan’s power reached its zenith in Colorado’s state politics in 1925.[7] In an atmosphere historian Melanie Shellenberger describes as “…a mixture of segregation and integration, blatant discrimination and comparative tolerance,” Black Coloradans navigated an unstable racial landscape as they sought to opportunities to spend leisure time, as well as modest amounts of disposable income, to enjoy the outdoors.

Founding Lincoln Hills

In 1925, E.C. Regnier and Roger E. Ewalt formed Lincoln Hills Inc. and founded Lincoln Hills near Pinecliffe, Colorado. The men’s racial identity is mysterious; while community oral history recalls them as Black, official census records recorded the men as white.[8] Whatever their race, the men clearly understood the local Black community and seemed to genuinely wish to improve Black access to the mountains. Regnier and Ewalt’s development was located less than forty miles from Denver in the Coal Creek Canyon alongside a stretch of South Boulder Creek exceptional for its trout fishing. The location offered easy, inexpensive transportation from the city by railroad or automobile. Small (twenty-five by 100 foot) mountain lots cost only $50, and the company offered simple financing at $5 down and $5 per month. Regnier and Ewalt advertised Lincoln Hills throughout the country. Property owners were mostly from Colorado, but also hailed from other states including Nebraska, Kansas, Wyoming, Missouri, Illinois, and Oklahoma, among others.[9]

Black community leaders in Denver enthusiastically endorsed Lincoln Hills because they saw the project as meaningful to their community. In 1926, Pastor of the Zion Baptist Church, G. L. Prince, purchased four lots himself, and spoke to the benefits of the mountains as a “tonic” for overwork, noting Lincoln Hills as “a place where our race can show to the Nation a constructive piece of work, in the upbuilding of a great National gathering place for health, recreation, education, and uplift.”[10] The language Prince and others chose in articulating Lincoln’s Hills’ importance was a clear nod to racial uplift politics, an important early 20th century Black social movement.

The Only Black Resort in the Mountain West

As the sole Black resort in the Mountain West, Lincoln Hills attracted entrepreneurs, pastors, doctors, and other professionals—precisely the kinds of people who participated in racial uplift politics. Black people committed to racial uplift sought self-improvement, respectability, and economic productivity as an avenue towards civil rights, as well as to American whites’ respect and acceptance.[11] Racial uplift was also compatible with more direct forms of political advocacy and action as well. The Cosmopolitan Club, an organization founded in 1931 by Clarence Holmes, promoted interracial and interfaith tolerance among Denver progressives.[12] Holmes and his wife hosted at least one club meeting at Lincoln Hills in 1937.[13] In this context, Lincoln Hills property owners were not just purchasing themselves a convenient scenic getaway. Consciously or not, they were also buying themselves a symbol of prosperity and self-sufficiency. The property they purchased also allowed them to enact socially meaningful rituals of respectability and self-improvement through outdoor recreation—a political act that subverted the exclusive racial norms American whites implemented to control space in the Colorado mountains.

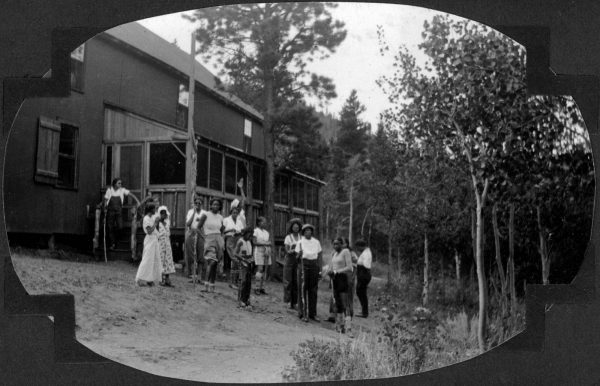

As they made informal claims to ostensibly public land, whites formalized their claims through segregation on private land. Only a handful of miles up the canyon from Lincoln Hills, Wondervu, a development created for working-class vacationers, was “…restricted to mountain homes for white persons.” While the reasoning behind Wondervu’s racial covenants could have been related to a variety of racist concerns, it is possible that developers wished to prevent Lincoln Hills residents from purchasing additional property elsewhere along the canyon.[14] Summer camps in the mountains were also subject to segregation. Barred from sending girls to segregated YWCA camps, the Phillis Wheatley branch of the Denver YWCA established Camp Nizhoni on a piece of land donated by Lincoln Hills, Inc. in 1924, and operated it until the YWCA integrated its facilities in 1946.[15] Once there, girls practiced outdoor skills such as hiking, swimming, and cooking over open fires, supervised by YWCA members. A YWCA girl reserve, Marie L. Anderson Greenwood recalled that running the camp appealed to her because, “It was an experience I had never had in my life… I loved the out-of-doors and nature and I found in Camp Nizhoni the thing that just made me happy.”[16] As Historian Miya Carey comments, “African American women framed access to camping as a civil rights issue, namely the right for black girls to have equal access to a healthy and happy childhood.”[17] Ensuring Black girls’ access to outdoor recreation and camping was not simply a matter of recreation, but carried political weight as well.

“Our Own Private Kingdom”

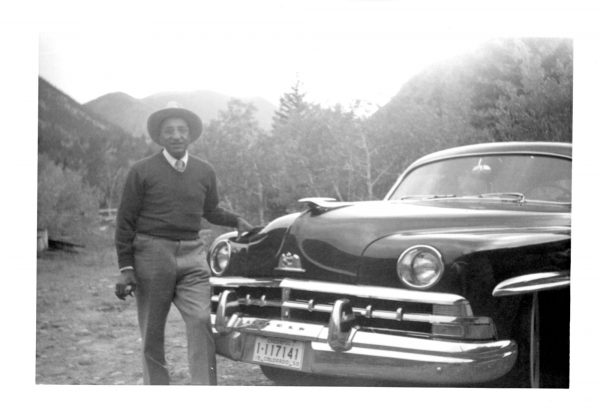

Alongside its social and political significance, Lincoln Hills provided Black people with treasured memories of the Colorado Mountains. O.W. Hamlet wrote of visiting his mountain cabin: “It’s the keenest pleasure I have ever known. It thrills and fills me with love for the out-of-doors and I am finding more genuine fun, health, and happiness for both my friends and myself…”[18] Hamlet, also known as “Winks,” founded Winks Lodge in Lincoln Hills in 1928, building the handsome, three-story, six-bedroom building himself out of local materials, and operated the lodge until his death in 1965.[19] Hamlet was a self-made man and an entrepreneur many times over. Described by his family as “a character,” he would personally collect his guests from the train station and drive them to the lodge.[20] Winks wanted to share his passion for Colorado’s natural environment and give others the opportunity to experience it for themselves, particularly Black youth.[21] Linda Tucker Kai Kai, Winks’ great-grandniece and Gary Jackson, Winks’ grandson, recalled the bustling lodge was “Our own private kingdom,” and “a safe haven.”[22] Winks advertised the lodge in the vacation section of the Negro Motorists’ Green Book from 1953-1957, and also placed ads in Ebony.[23] The lodge became the social heart of Lincoln Hills, boasting exceptional food cooked by Melba Hamlet, Winks’ second wife, and parties that stretched into the wee hours. Winks Lodge also hosted literary salons in the style of the Harlem Renaissance, and attracted black literary and musical luminaries including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington, among others.[24]

Conclusion

Lincoln Hills experienced a sharp downturn in the Great Depression. Although many individual properties were lost or abandoned, the lodge held on. Later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened new recreational opportunities to Black people, drawing remaining vacationers away from Lincoln Hills. Hamlet’s death a year later, generational changes in recreation, and the subsequent closure of Winks Lodge dealt the community repeated blows.[25] Over the following years, the lodge passed through various hands, including those of Bertha Calloway, an African American historian who added the lodge to the National Register of Historic Places. For a time, Winks Lodge was also owned by the James P. Beckwourth Mountain Club, an organization dedicated to providing outdoor recreation experiences to Coloradans of color.

Today the property is managed by Lincoln Hills Cares, a non-profit founded by Black Denver developer and founder of the Lincoln Hills Fly Fishing Club, Matthew Burkett, and Robert F. Smith. The Lincoln Hills Cares Foundation acknowledges that people of color have overwhelmingly been left of out careers in land management and cultural heritage, and that people of color still lack access and opportunities to experience Colorado’s natural spaces. It seeks to foster environmental leadership through historical education and outdoor recreation opportunities among youth of color at Lincoln Hills, continuing Hamlet’s legacy of sharing the Colorado mountains with a diverse public.[26] For organizations like Lincoln Hills Cares, educating youth about this community’s story is a corrective that challenges the enduring misconception that Black people did not enjoy nature in the past, and that their underrepresentation in natural spaces in the present is itself natural.

– Ariel Schnee, Public Lands History Center Program Manager

Published 10/14/2020

[1] Moore, Jesse T. Jr. “Seeking a new life: Blacks in post-Civil War Denver.” The Journal of Negro History. (Summer 1993) vol. 78 no. 3: 171, 175, 178.

[2] “Denver Needs a Vigilance Committee: A Call to Arms,” The Denver Star, September 20, 1913, Denver Public Library: Western History and Geneaology Department.

[3] “Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History,” Denver Public Library: Geneaology, African American and Western History Resources. https://history.denverlibrary.org/five-points-whittier-neighborhood-history, Accessed July 23, 2020.

[4] Simmons, Thomas H. Denver Neighborhood History Project, 1993-1994. Denver Public Library, Western History and Geneaology Department, 53.

[5] Shellenberger, Melanie. High country summers: The early second homes of Colorado, 1880-1940. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012, 127-129.

[6] Shellenberger, Melanie. High country summers: The early second homes of Colorado, 1880-1940. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012, 129.

[7] Noel, Tom. “When the KKK ruled Colorado: Not so long ago.” Blog post. Denver Public Library. https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/when-kkk-ruled-colorado-not-so-long-ago. Accessed July 9, 2020.

[8] National Register of Historic Places Form: Winks Panorama. National Park Service, 17. https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/13001035.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020. And Shellenberger, Melanie. High country summers: The early second homes of Colorado, 1880-1940. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012, 129.

[9] “Lincoln Hills.” Colorado Encyclopedia. https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/lincoln-hills . Accessed July 7, 2020. And National Register of Historic Places Form: Winks Panorama. National Park Service, 19. https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/13001035.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020. And Lincoln Hills Warranty Deed List. Lincoln Hills Company. Denver Public Library. ARL39. Lincoln Hills records. Box 1, Folder 13.

[10] G.L. Prince to Lincoln Hills, Inc. March 17, 1926. Denver Public Library.

ARL39. Lincoln Hills records. Box 1. Folder 5.

[11] “Booker T. Washington and the ‘Atlanta Compromise.’” National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/booker-t-washington-and-atlanta-compromise. Accessed July 9, 2020.

[12] “Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History,” Denver Public Library: Geneaology, African American and Western History Resources. https://history.denverlibrary.org/five-points-whittier-neighborhood-history, Accessed July 23, 2020.

[13] The Cosmopolitan Club of Denver, Official Records. Denver Public Library, Western History and Genealogical Collections, WH1270. Clarence and Fairfax Holmes papers, 1911-1974, 1890-1978.

[14] Standish, Sierra and Thomas, Adam. “Wondervu Historical and Architectural Survey, 2009-2010.” Boulder County Parks and Open Space, July, 2010, 23.

[15] “Camp Nizhoni.” Lincoln Hills Cares. http://lincolnhillscares.org/winks-panorama-2/#:~:text=Camp%20Nizhoni%20%E2%80%93%20Historical%20African%20American,YWCA%20camps%20as%20white%20children. Accessed July 10, 2020. And National Register of Historic Places Form: Winks Panorama. National Park Service, 20. https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/13001035.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020.

[16] Marie L. Anderson Greenwood, quoted in “Lincoln Hills.” Colorado Experience. Documentary Film Series. Rocky Mountain PBS. 21:14.

[17] Carey, Miya. “Becoming ‘A force for desegregation:’ The Girl Scouts and Civil Rights in the Nation’s Capital.” Washington History, (Fall 2017) Vol. 29, No. 2: 54.

[18] O.W. Hamlet to Lincoln Hills, Inc. January 24, 1928. Denver Public Library.

ARL39. Lincoln Hills records. Box 1, Folder 8.

[19] “Lincoln Hills.” Colorado Experience. Documentary Film Series. Rocky Mountain PBS.

[20] Linda Tucker Kai Kai, quoted in “Lincoln Hills.” Colorado Experience. Documentary Film Series. Rocky Mountain PBS. 16:16.

[21] “Lincoln Hills.” Colorado Experience. Documentary Film Series. Rocky Mountain PBS.

[22] Linda Tucker Kai Kai and Gary Jackson, quoted in “Lincoln Hills.” Colorado Experience. Documentary Film Series. Rocky Mountain PBS. 16:16 and 16:51.

[23] The Negro Motorists’ Green Book New York Public Library. Digital Collections. Accessed July 6, 2020. And National Register of Historic Places Form: Winks Panorama. National Park Service, 17. https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/13001035.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020.

[24] Winks Lodge. Colorado Encyclopedia. https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/winks-lodge. Accessed July 9, 2020. And National Register of Historic Places Form: Winks Panorama. National Park Service, 36-38.

[25] National Register of Historic Places Form: Winks Panorama. National Park Service, 17. https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/13001035.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020.

[26] National Register of Historic Places Form: Winks Panorama. National Park Service, 17-18. https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/13001035.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020.