A City Without Cars

In the late 1800s, Denver’s transportation infrastructure was built for the convenience of pedestrians, rather than drivers. Denver’s historic streetcar system was an efficient way for people to move throughout the city and helped develop community ties among riders. A little under a century later, Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD), was struggling to maintain the same level of public use and support. As the city’s wealth gap grew, middle- and upper-class commuters increasingly preferred the privacy and flexibility of private vehicles. Now, the RTD system needs to change again, balancing the city’s historic culture of commuting collectively with the preferences of contemporary riders.

The Streetcar System

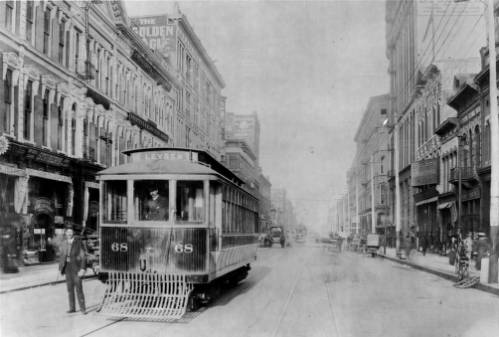

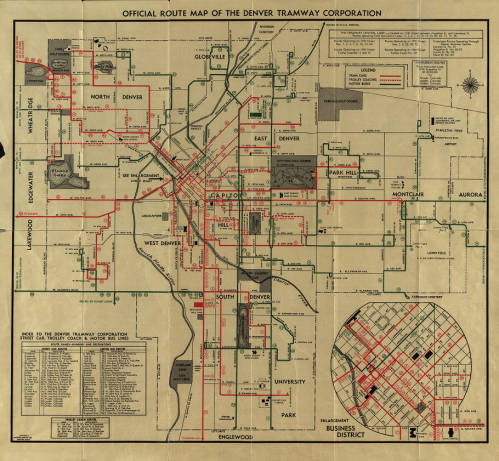

At the dawn of the 1900s, streetcar systems were booming. Denver’s first public transportation system was a horse-drawn rail carriage that went from Auraria to Curtis Park, built by the Denver Horse Railroad Company (later, the Denver City Railway) in 1871. Curtis Park is known as Denver’s first “streetcar suburb.”[1] The invention was a huge success.[2] A competitor, the Denver Tramway Company (DTC), further expanded transit options, and had applied cable car technology to their streetcars by 1888. Fierce competition for territory among different tram and streetcar companies and rapidly advancing technology meant that, by 1890, nearly every block in the city had a streetcar line. While electric streetcars had been in use since 1885, early versions were hazardous. By the 1890s, the technology had improved. Overhead wires replaced electrified third rails installed at street level, preventing electrocutions during wet weather. The electric streetcar eventually replaced all other types of lines.[3]

In 1915, more than fifty-one percent of the city’s population rode streetcars as their primary mode of transport.[4] In early twentieth century Denver, people worked, shopped, and recreated in cultural hubs near streetcar stops. Public transit not only facilitated travel, but also created new spaces and opportunities for social interaction. Streetcar lines along Broadway and Colfax created community centers that still exist in Denver today.[5] The electrified streetcar remained the city’s most popular transportation system until 1950.[6]

Despite the streetcar’s popularity, automobiles ultimately became the preferred method of transport in Denver.[7] A Ford production plant was built in 1913 and began producing the inexpensive and popular Model T in 1914.[8] The DTC, which owned most streetcars at the time, converted entirely to bus service by midcentury, but even bus ridership declined as more Denverites purchased their own cars over time.[9] Personal automobiles “enabled Denverites to move beyond the old walking city and its streetcar suburbs.”[10] The daily commute became more individual than communal.

As the city expanded, the wealthier classes grew to dislike “close, urban quarters,” and purchased homes still further from their jobs, their longer commutes made smoother and easier by the city’s expanding road network. Those who could not afford to live outside of the city stayed where they were.[11] As Denver’s wealth and class divisions widened, so too did the physical distance between the city’s more and less affluent neighborhoods.

Building the Regional Transportation District

Decades of flight to the suburbs and the decline of public transit had unforeseen consequences. By 1931, roughly 251,363 Denverites used cars while only 152,991 rode streetcars.[12] Backed by the wealthy, city planners and politicians promoted the use of cars, which in turn discouraged public transport and eventually eliminated rail lines from the streets.[13] However, city leaders’ love affair with the automobile soured as heavy traffic clogged Denver’s roads. The DTC, which had presided over much of Denver’s transit history, was nearly bankrupt by 1969. The City of Denver purchased the company’s assets in 1971. In 1973, Denver voters approved a tax supporting the new Regional Transportation District (RTD).[14] Automobile traffic was described as “the most sinister disease that has ever affected the welfare of large American cities.”[15] The Regional Transportation District (RTD) was developed as a way to restore Denver’s once-robust transit system and resolve its traffic woes.

By 1980, the RTD light rail system had been built and was becoming more popular. “Busses are great, but they can’t do everything,” remarked RTD board member, Roger DeVries, to the Douglas County News Press.[16] Today, eight Colorado counties are included in the RTD system. The light rail has 60.1 miles of track, stops at 57 stations, and includes 201 light rail vehicles.[17]

Looking to the Future of Transportation

As of 2019, Denver’s rail line had over 133 million annual boardings.[18] This number dropped drastically during the 2020 pandemic, to just over 15 million annual riders.[19] As of January 2022, “the drop [of ridership] is most severe on lines that serve suburbs… while lines that go through dense areas with low-income residents have stayed relatively steady.”[20] Brian Welch, RTD senior manager for planning technical services, indicated that the RTD should focus on serving neighborhoods that rely on public transportation more than personal cars.[21] He said that the RTD will “put money in places in which people are riding, and figure out other solutions where people aren’t.”[22]

Denver residents are looking for alternatives to driving, which has helped RTD ridership bounce back post-pandemic.[23] Recent rail extensions to Denver International Airport, Aurora, and Golden have helped bring more RTD riders.[24] However, cars remain the most popular option, especially for commuters. In 2016, over seventy percent of Denver workers still commuted by car, but Mayor Hancock hoped to see substantial drop in that number by 2030 by expanding the RTD system.[25] Expanding the RTD will take time, but city leadership is also embracing more immediate opportunities by partnering with bike shares and electric scooter companies.

Launched in May 2021, Denver’s Shared Micromobility Program is a scooter and bike share initiative. The program involves the City of Denver and the private companies Lyft and Lime.[26] The program allows riders to inexpensively rent scooters and bikes to travel around the city. Riders can rent a Lyft bike for three dollars a month, or use a Lime scooter for two dollars an hour.[27 ] Every day, thousands of people use these services.[28] Unlike light rail or bus travel, bikes and scooters allow their riders to travel on their own schedules to whatever destinations they choose.

What Comes Next for Transportation?

Denver’s traditional public transit system does not have to compete with the micromobility program for riders. If light rail systems partnered with scooter and bike share programs, a multimodal public transportation system could be created. Waterloo’s School of Computer Science proposed this idea in 2018 and advised it to cities with strong public transportation systems.[29] In a multimodal system, riders would rent an electric bike or scooter to go from their home to a light rail station, arrive in a new part of the city, and ride another bike or scooter to their final destination.[30] This collaboration would mesh the ability to travel farther distances via RTD rail with the flexibility of scooter and bike share programs.

Is multimodal transit feasible in Denver? The increasing interest in micromobility programs certainly suggests so. Historically, Denver public transportation adapted to new technological advancements and the public’s changing needs. Preserving and expanding traditional public transit, like the light rail, while also embracing scooter and bike share programs, could be the key to increasing RTD ridership and improving public transportation for all. As Denver recovers from the pandemic, there is hope that the light rail system will flourish as history meets the modern-day.

-Lauren Hennessey, PLHC Intern

Published 05/03/2022

Sources

[1]Ryan Keeney, “The History of Denver’s Streetcars,” accessed April 6, 2022, https://denverurbanism.com/2017/08/the-history-of-denvers-streetcars-and-their-routes.html#:~:text=In%201872%20the%20Denver%20Horse,Auraria%20to%20modern%20Curtis%20Park.

[2]Colorado Encyclopedia, s.v. “Denver Tramway Company,” accessed April 6, 2022, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/denver-tramway-company.

[3]Keeney, “The History of Denver’s Streetcars.”

[4]Keeney, “The History of Denver’s Streetcars.”

[5]Stephen J. Leonard and Thomas J. Noel, Denver: Mining Camp to Metropolis (University Press of Colorado, 1990), 265.

[6]Golden Triangle Auto Care, “Denver’s Early Car Manufacturing,” accessed April 14, 2022, https://goldentriangleautocare.com/denver-early-car-manufacturing/.

[7]Stephen J. Leonard and Thomas J. Noel, Denver: Mining Camp to Metropolis, 53.

[8]Stephen J. Leonard and Thomas J. Noel, Denver: Mining Camp to Metropolis, 53.

[9]Ibid, 58.

[10]Ibid, 64.

[11]Ibid, 266

[12]Ibid, 266.

[13]Ibid, 266.

[14]Ibid,269

[15]Jerry Peterson, “Former RTD board member urges ‘yes’ vote on light rail,” Douglas County News-Press, (June 19, 1980) in the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection, accessed April 6, 2022, https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=DNP19800619-01.2.3&srpos=10&e=——-en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-rtd+system+public+opinion——-0——.

[16]“Facts and Figures: RTD by the Numbers,” RTD, last modified April 2021, accessed April 6, 2022, https://www.rtd-denver.com/reports-and-policies/facts-figures#:~:text=The%20Regional%20Transportation%20District%20was,Boulder.

[17]“Facts and Figures: RTD by the Numbers.”

[18]“Facts and Figures: RTD by the Numbers.”

[19]Nathaniel Minor, “RTD proposes massive overhaul: Fewer Suburban buses, more service were riders remained during the pandemic,” CPR News, January 12, 2022, accessed April 27, 2022, https://www.cpr.org/2022/01/12/rtd-bus-network-overhaul/.

[20]Nathaniel Minor, “RTD proposes massive overhaul: Fewer Suburban buses, more service were riders remained during the pandemic.”

[21]Ibid

[22]Letters, opinion, Denver Post, March 20, 2022, accessed April 6, 2022, https://www.denverpost.com/2022/03/21/rtd-needs-help-funds-ridership/.

[23]“Facts and Figures: RTD by the Numbers.”

[24]Dave Burdick, ”People are commuting alone in cars less, but Denver’s a long way from its goals,” Denverite, Last Modified September 17, 2018, Accessed April 14, 2022, https://denverite.com/2018/09/17/people-are-commuting-alone-in-cars-less-but-denvers-a-long-way-from-its-goals/.

[25]“Denver’s Scooter and Bike Share Program,” Denver, last modified June 2021, Accessed April 7, 2022. https://www.denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Department-of-Transportation-and-Infrastructure/Programs-Services/Transit/Micromobility-Program.

[26]“Denver’s Scooter and Bike Share Program,” Denver.

[27]Ibid

[28]University of Waterloo, “Bikeshare could increase light rail transit ridership,” Science Daily, June 8, 2018, accessed April 6, 2022, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/06/180608003222.htm.

[29]“Facts and Figures: RTD by the Numbers.”

[30]University of Waterloo, “Bikeshare could increase light rail transit ridership.”