The Origins of Sin City

Saddled with gleaming skyscrapers and picturesque fountains, the streets of Las Vegas suddenly emerge amongst red-rimmed mesas in the Mojave Desert. Sin City offers a shimmering respite from the desert that surrounds it, a consumerist paradise set along sandstone and tumbleweeds, but it wouldn’t exist if Hoover Dam was never constructed. The dam made Las Vegas’ growth during the 20th century possible. However, the federal government devolved the burden of water conservation to local authorities, who grappled with the problem of drought by adapting water policy to manage the city’s water use in the 21st century.

Black Canyon in 1922, before it went underwater with the creation of Hoover Dam and Lake Mead. Accessed 10/10/2021, https://grcahistory.org/sites/beyond-park-boundaries/lake-mead.

Black Canyon in 1922, before it went underwater with the creation of Hoover Dam and Lake Mead. Accessed 10/10/2021, https://grcahistory.org/sites/beyond-park-boundaries/lake-mead.

Cultivating Economic Prosperity – and Recreation

In 1928, Congress passed the Boulder Dam Project Act to develop a reservoir on the lower Colorado River. Its creation had three purposes: the dam would control flooding, provide water for irrigation and residential uses, and generate hydroelectric power.[3] By 1931, the Bureau of Reclamation had begun building Boulder Dam (later renamed Hoover Dam) just outside of Las Vegas’ city limits.[4] The project stimulated the region’s economy and made it possible for the city to begin growing again.

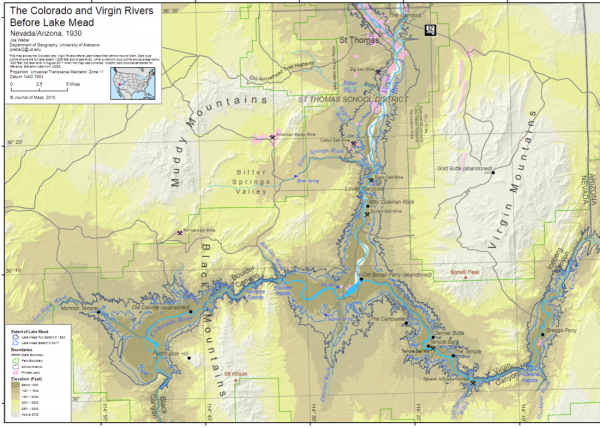

A map of the Colorado and Virgin rivers before they were flooded by Lake Mead, compiled from 1930 data sets. Accessed 10/5/2021, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17445647.2018.1517700.

A map of the Colorado and Virgin rivers before they were flooded by Lake Mead, compiled from 1930 data sets. Accessed 10/5/2021, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17445647.2018.1517700.

In 1936, Lake Mead was established as the country’s first national recreation area after the dam’s completion. The Boulder Dam project enabled the Las Vegas Valley to rebound from the Great Depression; its federal stimulus stabilized the local economy, prevented mass unemployment, and avoided bank closures.[5] Roosevelt’s New Deal further helped the city transform from “a whistle-stop to a thriving city,” as programs funded paved roads and a centralized sewer system.[6] By mid-century, Las Vegas had become an established tourism and recreational hub, as the infamous Las Vegas strip began to emerge. Americans wanting to erase the memories of the “hard years” after World War II visited Lake Mead in droves to swim and recreate.[7] A picturesque oasis surrounded by red-rimmed mesas, Lake Mead’s allure has only grown in the past 60 years. Visitors made more than 7.5 million trips to Lake Mead in 2018, making it the sixth most visited national park in the United States.[8]

Creating a Sustainable Water Use Policy

Federally funded water projects like Lake Mead and Hoover Dam allowed Las Vegas to grow and prosper in the mid-twentieth century. But in the twenty-first century, climate change has forced local authorities to implement water conservation measures to survive. Historically, groundwater supplies had been enough to meet Vegas residents’ thirst for this precious desert resource, but demand from a growing population soon outstripped supply. In 1980, the Las Vegas region began allocating water from Lake Mead for residential use. By 1996, the Las Vegas Water Authority decided to implement the “cash for grass” initiative, which paid residents to not plant grass.[9] In the past 25 years, the program has been very successful, with one Harvard study finding that it reduced average water use by 21%.[10] According to CSU history professor Michael Childers, Las Vegas now puts more water back into the Colorado River than it takes out. This means that the Colorado River tangibly benefits from Las Vegas’ water regulations— despite the city’s high-profile golf courses, lavish swimming pools, and iconic fountains dotting the strip. These policies are an example of successful water management. Changing residential water use patterns was an overdue adaptation to the local environment in Las Vegas. As more and more of the West struggles with drought, other cities will need to look to these policies as necessary adaptations to climate change.[11]

Using Water Wisely?

While the Las Vegas Water Authority has been successful in lowering its water consumption, it represents how responsibility for water management has devolved from the federal to local level since the New Deal. Local authorities are now tasked with addressing the impacts of drought and managing water resources, even though the West’s often maladapted water sources were developed by federal entities. Las Vegas demonstrates how Lake Mead’s built environment prioritized urban growth over sustainability. Ultimately, the Mojave’s unforgiving climate won out.

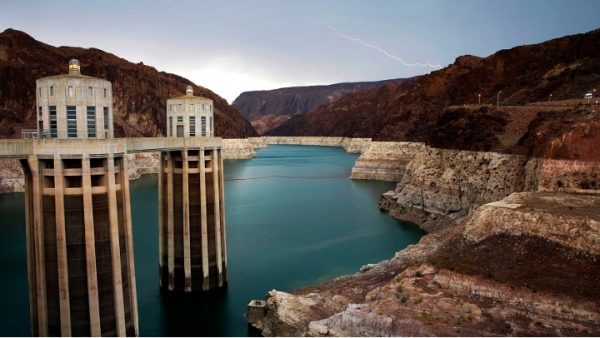

Lake Mead has experienced unprecedented drought in the past 30 years, which has led to record low water levels that created a “bathtub ring” on sandstone previously underwater. Accessed 10/19/2021, https://www.8newsnow.com/news/local-news/projections-show-lake-mead-dropping-far-below-governments-shortage-level/.

Lake Mead has experienced unprecedented drought in the past 30 years, which has led to record low water levels that created a “bathtub ring” on sandstone previously underwater. Accessed 10/19/2021, https://www.8newsnow.com/news/local-news/projections-show-lake-mead-dropping-far-below-governments-shortage-level/.

Las Vegas’s water story is a lesson for the greater American West. Western landscapes, and particularly urban landscapes, have been manipulated to create the illusion of robust, water-rich environments. The illusion has become so convincing that it conceals their underlying fragility and delays policy change until the point of crisis. Despite dwindling supplies, states with greater water allocations from the Colorado River Compact such as Colorado and Arizona have yet to take enough action to rein in their water use.[12] If people want to thrive in the American West, cities and states alike must reevaluate their water consumption in places that are only going to become hotter and drier with time – despite the compelling mirages that challenge the landscapes around them and suggest otherwise.

— Corinne Neustadter, PLHC Intern

[1] Eugene P. Moehring and Michael S. Green, Las Vegas: A Centennial History (Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 2005), 2.

[2] Moehring and Green, 11-13.

[3] Douglas W. Dodd, “Boulder Dam Recreation Area: The Bureau of Reclamation, the National Park Service, and the Origins of the National Recreation Area Concept at Lake Mead, 1929-1936,” Southern California Quarterly 88, no. 4 (Winter 2006-2007), 432-433.

[4] Eugene P. Moehring and Michael S. Green, Las Vegas: A Centennial History (Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 2005), 81-83.

[5] Moehring and Green, 91.

[6] Ibid, 93.

[7] Ibid, 106-107.

[9] Jonathan E. Baker, Subsidies for Succulents: Evaluating the Las Vegas Cash-for-Grass Rebate Program,” Harvard Environmental Economics Program (Fall 2017), 2.

[10] Baker, 3.

[11] Conversation with Dr. Childers