Who Gets a Getaway?

The year was 1940. As World War II raged in Europe, and Americans seeking leisure and adventure turned to exploring their National and State Parks rather than vacationing abroad.[1] In the east, Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountain National Parks were open. Instead of trekking to the National Parks of the west, easterners could pack up their vehicles and travel to a National Park of their very own. State park systems had also begun to develop, encouraged and assisted by the National Park Service (NPS). But these newly-opened public lands were not fully accessible to everyone–especially if you happened to be black. At Shenandoah and other units throughout the South, the NPS built segregated segregated facilities and enforced local segregation laws. This legacy of denying African Americans full access to public lands continues to influence visitor demographics in the National Parks today.

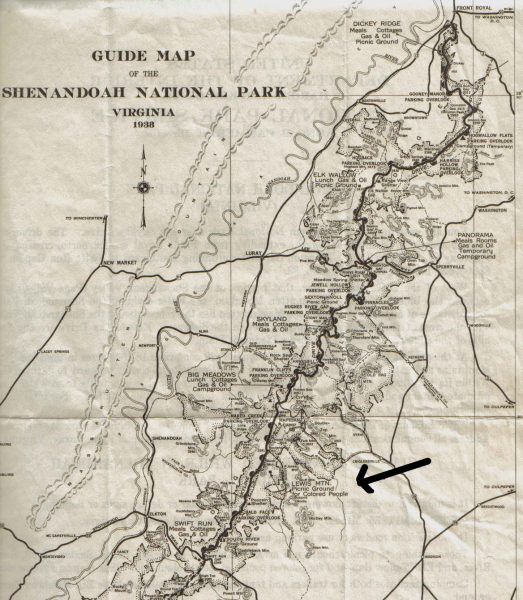

Segregation at Shenandoah National Park

In 1922, NPS park superintendents decided: “we cannot openly discriminate against [African Americans], [but] they should be told that the parks have no facilities for taking care for them.”[2] In the 1930s and 1940s, “black codes” mandated segregation. These laws proliferated at the state level, particularly in the south. Even though it was federal land, Shenandoah National Park was segregated through a “gentleman’s agreement.” In this agreement, the NPS committed to operate the park according to the state of Virginia’s local laws and customs, including segregation.[3]

On November 30, 1932, Cammerer, then Deputy Director of the NPS, wrote to Director Horace Albright about the development of segregated facilities at Shenandoah. He asserted that it was necessary to provide, “Provision for colored guests.”[4] Along with segregated sections of dining areas, lunch counters, picnic areas, and comfort stations located throughout the park, a separate picnic ground and campsite called Lewis Mountain was developed at the park as a “Negro Area.” The picnic area and campground at Lewis Mountain shared the same construction, materials, and design as the rest of Shenandoah, and were likewise constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The product of a racist and oppressive system, Lewis Mountain nevertheless provided African Americans with an opportunity, however limited, to access and enjoy recreation outdoors during the Jim Crow era.

Park leadership referenced this seeming parity in order to argue that the park was, in fact, successfully upholding the “separate but equal” clause that made segregation legal in the United States. However, this did not translate to an equality of experience, or to equal treatment. Segregation prevented African Americans from enjoying the same access and freedom of movement that white visitors enjoyed, and they received discriminatory treatment at the hands of the white park rangers who removed them from the park’s white-only spaces.[5]

Segregation at State Parks in the South

The National Park Service’s minimal attempt to provide black visitors with park facilities contrasted with the clear inequality of segregated facilities in the South’s state parks. Where African American parks did exist, they were either severely limited in size and quality, or attached as inferior sections of white parks and lacked access to historically significant places.[6] During the New Deal Era, southern states added 150 state parks and excluded African Americans from nearly every one.[7] During the 1930s and 1940s, the situation was rather dire for African Americans in terms of access to state parks. As Geographer and Historian William O’Brien writes, “African Americans would need to travel considerable distances to locate [a park] that would welcome them, and many would need to leave their states to find access.”[8] Whites were typically able to find and access a park within 50 or so miles of home.

Desegregation, not Integration

The road to de-segregation at Shenandoah was rocky. Resistance to de-segregation within the NPS’s own ranks resulted in the demotion and transfer of Shenandoah’s superintendent, J.R. Lassiter, as well as tense negotiations with the park’s concessionaire, the Virginia Sky-Line company. Faced with the end of segregation, the company threatened to cease its operations in the park rather than integrate. At the state level, desegregation of parks came later, and was even rockier, involving years of lawsuits and park closures, lasting until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[9]

Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, quietly desegregated Lewis Mountain in 1945, and the entire National Park Service followed in 1950 with a similar lack of fanfare. Yet true desegregation would take years to fully develop in the National Park Service, an example of “de-facto” segregation is the continued segregation of the concession facilities at Lewis Mountain until 1950. This left African Americans unsure whether they had access to any accommodations in the National Parks at all. Many people wrote to the park individually, inquiring about facilities for camping, group tours, and busses, and had to be informed, one by one, that segregation was no longer practiced at Shenandoah.[10] Likely, many African Americans stayed out of the National Parks altogether, rather than risk traveling to places like Shenandoah only to be turned away.

Today, the National Park Service still struggles with a lack of diversity among its visitors, which it is attempting to resolve by reaching out to communities of color.[11] As the American population becomes increasingly racially diverse, the Park Service must find ways to heal these broken relationships, cultivate them anew, and apologize for its past mistakes. Only then can it reasonably expect taxpayers and voters to continue to invest in and advocate for the preservation of public lands. Telling the histories of people of color on public lands and acknowledging their all-too-recent mistreatment by the NPS is an important first step.

-Tim Johansen, PLHC Researcher

-Ariel Schnee, PLHC Project Manager

Sources

[1]“National Parks’ Homefront Battle: Protecting Parks During WWII,” National Park Service, last modified November 20, 2015, accessed September 21, 2018. https://www.nps.gov/articles/npshomefrontbattle.htm.

[2]Marguerite S. Shaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 126, quoted in Terence Young, “A Contradiction in Democratic Government: W. J. Trent, Jr., and the Struggle to Desegregate National Park Campgrounds,” Environmental History 14, no. 4 (October 2009), 652.

[3]Erin Krutko Devlin, “Under the Sky All of Us Are Free”: African American Travel, Visitation, and Segregation in Shenandoah National Park, July 2010, 34.

[4]Reed Engle, Resource Management Newsletter, January 1996, National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/shen/learn/historyculture/segregation.htm

[5]From Downing L. Smith, Shenandoah National Park, Ranger, to Stephens, Shenandoah National Park, Chief Ranger, July 28, 1940. SHEN Archives, Park Central Files, Box 30, Public Service—Negroes.

[6]For further reading on this topic, see William E. O’Brien, Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South, 2016.

[7]William E. O’Brien, Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016), 4-7.

[8]O’Brien, “State Parks and Jim Crow In The Decade Before Brown V. Board Of Education,” 174.

[9]“History of Virginia State Parks,” Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, http://www.dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/history, Accessed September 20, 2018.

[10]Shumaker, “Untold Stories from America’s National Parks, 32, and From Oliver G. Taylor, Shenandoah National Park, Chief of Public Services, To Mr. David D. Jones, June 16, 1950, SHEN Archives, Park Central Files, Box 30, Public Service—Negroes.

[11]Rebecca Stanfield McCrown, Daniel Laven, Robert Manning, and Nora Mitchell, “Engaging New and Diverse Audiences in the National Parks: An Exploratory Study of Current Knowledge and Learning Needs,” The George Wright Society, pp. 272. http://www.georgewright.org/292stanfield_mccown.pdf, Accessed September 20, 2018.