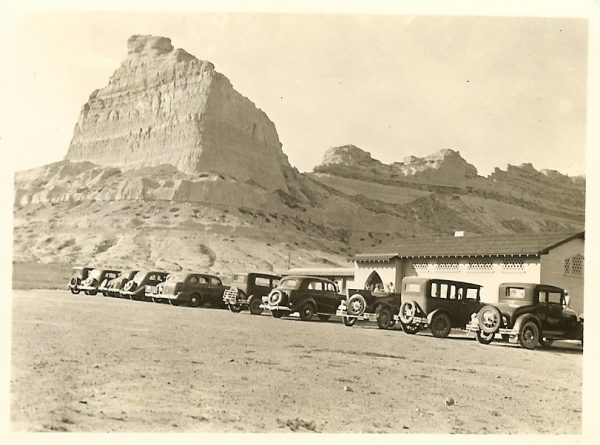

Adrift at Scotts Bluff National Monument

Alone on the mixed grass prairies of western Nebraska at Scotts Bluff National Monument, a wanderer might almost think themselves adrift on a rustling sea. The wind ripples and hisses. Sunlight glints white off millions of leaves and stalks. On the bewildering expanse distances warp and stretch. Gazing to the horizon, a mile distorts into ten, twenty, a hundred, then to endlessness. The sudden sight of a rocky island jutting above the unbroken plain steadies and reassures, a visual anchor. Reality reasserts itself. Distances resume their logical dimensions. A mile becomes a mile.

A Monument to Westward Expansion

President Woodrow Wilson designated the National Monument in 1919. Wilson recognized that migrants on the Oregon, Mormon and California trails imbued the distinctive rock formations with cultural meaning as landmarks on the western trails.[1] The Scotts Bluff represented a nationalist version of the history of westward expansion. That perspective centered and celebrated the experience of white, Euro-American, predominantly male, pioneers. However, when viewed as a cultural landscape, the National Monument can convey more than the history of a single group and the meaning they attached to the landscape. Within the National Park Service a cultural landscape is: “a geographic area (including both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife or domestic animals therein), associated with a historic event, activity or person or exhibiting other cultural or aesthetic values.”[2] Scotts Bluff National Monument is a prime example of what cultural landscape interpretation can do to tell more complex and inclusive public lands stories.

A Long Human History

The National Monument’s human and natural histories had already been intertwined millennia before the first pioneers set foot on the prairie. All humans need natural resources. They rely on and exploit sources of water, hunt animals, collect food, plant crops, and graze livestock. These activities create landscapes that are both human and natural. The North Platte River, the mixed-grass prairie, and its abundant wildlife, especially the American Bison, made the area around Scotts Bluff an attractive location for Paleo-Indian groups. Paleo-Indians entered North America between 28,000 and 10,000 years ago. By the 1700s, nomadic and village-based American Indian cultures, including the Cheyennes, Arapahos, and Pawnees, migrated west and adapted to Nebraska’s environmental conditions. In wetter (eastern) parts of Nebraska, agriculture dominated. To the west, nomadic tribes hunted bison on horseback across the arid plains. In the plains economy, tribes exchanged bison hides and meat for corn and garden produce.[3] Scarce water meant that the North Platte River held special significance. The Pawnees called the North Platte kisparuksti, or the “wonderful river.” Many of the places the Pawnees hold sacred are located along the river or on its tributaries.[4]

Westward Migration at Scotts Bluff National Monument

By the 1840s, migrants travelling to the far west on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails encountered an extreme landscape. During dangerous crossings of the Platte or sudden, violent prairie storms, the environment became an adversary.[5] To make the land seem more familiar, they named rock formations for symbols of social order and domesticity: courthouses, jails, and chimneys.[6] Near Scotts Bluff, the Platte offered a reprieve from the parched plains, and migrants also interpreted the landscape, particularly around the river, as a lush, inviting garden.[7]

Overhunting of buffalo herds, overland migration, the whiskey trade, disease, warfare, and federal removal efforts combined to decimate and displace the region’s native population over the course of the 1800s. As the far west filled, would-be settlers increasingly took their chances in western Nebraska’s arid environment. Many failed. In response, the 1904 Kinkaid Act ( an expansion of the 1862 Homestead Act), gave 640 acres of land free to settlers willing to risk dryland farming on the plains. Still, permanent settlement in western Nebraska came slowly. Settlers saw constant challenges from locusts, drought, and the isolation and poverty of agricultural life on the plains, and many abandoned their claims.[8]

The North Platte Project: Irrigating the Plains

The advent of the railroad, as well as large-scale irrigation projects in the late 1800s and early 1900s began a new, intensified chapter in the relationship between humans and Scotts Bluff’s landscape. The railroad allowed people to travel west more quickly, aggressively advertised and sold company-owned land next to the railway tracks, and provided a much-needed link to agricultural markets. The Bureau of Reclamation’s North Platte Project allowed farmers to exploit and control the waters of the Platte in unprecedented ways. Furthermore, industrial-scale agriculture, namely sugar beet and livestock cultivation, brought economic advancement and stabilized the region’s population. Irrigating the plains came at a steep environmental cost. As farms grew steadily larger throughout the late 1900s, the Platte could no longer meet Nebraskan farmers’ need for water. Increasingly, they turned to the Ogallala Aquifer to fill the gap. Currently, climate change and over-exploitation of the region’s surface and groundwater supplies routinely brings farmers and urban dwellers into conflict over water.[9]

Change as a Constant at Scotts Bluff National Monument

In a landscape marked by transience and change, interaction between humans and the land is a constant in the National Monument’s history. Interpreting this land as a series of layered and intersecting cultural landscapes unites what seems like a fragmented narrative. This methodology represents a greater variety of land uses by different groups, and deepens the public’s understanding of the land’s significance. Additionally, this perspective brings forth questions about humans’ relationships to the natural world at this moment in history. The history of Scotts Bluff is far more than that of the overland trails, and the national monument is increasingly recognizing that in order to remain relevant, it must embrace all of its history. Redesigned and updated exhibits are now on display at the National Monument’s visitor center. The National Monument is also the subject of a multi-disciplinary, interactive Story Map and an updated historical booklet for visitors, completed through a Collaborative Ecosystems Study Unit (CESU) project with the Public Lands History Center in 2017.

-Ariel Schnee, PLHC Project Manager

Published 10/31/2018

Sources

[1] “Proclamation of Establishment, December 12, 1919,” in Ron Cockrell, Administrative History of Scotts Bluff National Monument, Appendix B.

[2] “Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes: Defining Landscape Terminology,” The National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/tps/standards/four-treatments/landscape-guidelines/terminology.htm. Accessed June 28, 2018.

[3] Poppie Gullet, Ariel Schnee, and Andrew Cabrall, “Challenges to American Indian Lifeways, 1800-1880,” Scotts Bluff National Monument: In-Depth Historical Research and Documentation, ed. Ruth A. Alexander, Poppie Gullet, and Ariel Schnee, (2017: Scotts Bluff National Monument), 53.

[4] Douglas Sheflin, “The Changing River,” Scotts Bluff National Monument: In-Depth Historical Research and Documentation, ed. Ruth A. Alexander, Poppie Gullet, and Ariel Schnee, (2017: Scotts Bluff National Monument), 137.

[5] Nicholas Gunvaldson, “Encountering the Unfamiliar: Society, Geology, and Race Along the Overland Trail, 1840-1869,” Scotts Bluff National Monument: In-Depth Historical Research and Documentation, ed. Ruth A. Alexander, Poppie Gullet, and Ariel Schnee, (2017: Scotts Bluff National Monument), 101.

[6] Nicholas Gunvaldson, “Encountering the Unfamiliar: Society, Geology, and Race Along the Overland Trail, 1840-1869,” Scotts Bluff National Monument: In-Depth Historical Research and Documentation, ed. Ruth A. Alexander, Poppie Gullet, and Ariel Schnee, (2017: Scotts Bluff National Monument),106-109.

[7] Douglas Sheflin, “The Changing River,” Scotts Bluff National Monument: In-Depth Historical Research and Documentation, ed. Ruth A. Alexander, Poppie Gullet, and Ariel Schnee, (2017: Scotts Bluff National Monument), 141.

[8] Douglas Sheflin, “From Highway to Destination: Homesteading the Panhandle 1880-1900,” Scotts Bluff National Monument: In-Depth Historical Research and Documentation, ed. Ruth A. Alexander, Poppie Gullet, and Ariel Schnee, (2017: Scotts Bluff National Monument), 171.

[9] Ariel Schnee, Scotts Bluff National Monument: A Natural and Human History of American Westward Expansion, (2018: Scotts Bluff National Monument).