The following is a repost from History Colorado’s Weekly Digest that appeared in the August 21st edition under the title “Race and Ranching in Rocky Mountain National Park.” To visit the original post, click here.

A Visit to McGraw Ranch

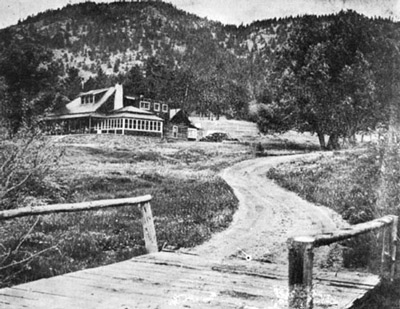

One cold blue August morning, I opened the door of my tiny cabin at the Continental Divide Research Learning Center’s McGraw Ranch in Rocky Mountain National Park. I listened to the burbling of Cow Creek and gazed to the mountains, drenched in gold from the rising sun. The value of McGraw Ranch, however, is more than scenic. Its enduring physical presence tells histories that interweave the environment, race, and leisure in Colorado. At Rocky Mountain National Park’s historic dude ranches, Western promoters (especially railroads), dude ranchers, and visitors claimed Colorado’s mountains as white racial space, and reserved western tourism and the enjoyment of western landscapes as the cultural and physical domain of whites.

Well before McGraw Ranch started opening its doors to guests, nineteenth century American elites, most notably Theodore Roosevelt, had reached a definitive consensus on the value of spending time (and money) to experience the American West’s mountain landscapes.[1] The perceived purpose of Western travel morphed subtly between the Civil War and World War II, and western tourism extended down the social scale. Engaging with nature (preferably in as wild a state as possible) had become a tonic for white Americans’ anxieties about the impending loss of racial vigor—the perceived result of less strenuous forms of work, rising racial diversity, and comparatively leisured urban lifestyles.[2] By the 1930s and 1940s, rising wages, more vacation time, and improved travel infrastructure made recreating in the West’s national parks accessible to working class vacationers, although they mainly stayed in campgrounds, rather than ranches or lodges.[3] As the Union and Pacific Railroad suggested, a stay at a Colorado guest ranch (and the use of its convenient rail service to get there) was the solution for weary urbanites seeking invigorating vacations for themselves and their children.[4]

Guest Ranching at Rocky Mountain National Park

Guest ranches had been an important part of the national park’s tourist infrastructure since the early twentieth century. They offered visitors lodging, food, and recreation alongside a hefty dose of Western culture. Widowed in 1918, Irene McGraw, the McGraw family matriarch, ran the ranch while raising three sons and a daughter. She was also deeply involved in Estes Park’s community and intellectual life. She often hosted card games, dinners, music clubs, salons, and supported local charitable efforts within the Estes Park community.[5]

Falling agricultural prices in the 1920s meant that the family pursued several means of producing income from the land, including selling dairy, meat, and lumber. In 1936, McGraw Ranch began catering to tourists, starting with Republican candidate for U.S. presidency, Alf Landon. Along with his family, Landon made the ranch his summer campaign headquarters.[6] The transition into guest ranching was organic for the McGraws, as the family had always had a busy social life.[7] Irene McGraw continued to operate the property as a working cattle ranch while taking in guests.[8] Staying at the McGraw ranch offered visitors “…a vacation you will never forget” complete with rugged recreation like big game hunting, pack trips, riding, and fishing alongside modern comforts, like “dinner parties,” “excellent food,” and “good beds” in a climate “air-conditioned by nature.” Irene McGraw’s son, Frank McGraw, worked to promote Colorado’s guest ranches at the state and national levels. In 1941, the Colorado Dude and Guest Ranch Association elected McGraw as one of its directors. Frank McGraw was also a key organizer of the Estes Park Rodeo, helping to restart the local tourist attraction in 1946 after a several years-long hiatus during WWII.[9] As ranchers who also participated in the area’s tourist economy, the McGraws thoroughly understood the appeal of their land and lifestyle and recognized tourism’s role in sustaining the ranch’s other lines of business.[10]

Ranching and White Racial Space

The value of the guest ranch experience was rooted in an understanding of ranches and the lands they occupied as white racial space. Western tourists were also consumers of popular culture that taught them to envision ranching and the occupation of ranch hands or cowboy as intimately related to white, male American identity. Similarly, ranching was an occupation that symbolized the cultural ideals of personal freedom, physical vigor, and the development of longstanding, meaningful relationships with western landscapes. The misunderstanding of the racial makeup of a working ranch experience as primarily white contradicted the reality of ranching as part of a global system of industrial food production. People of color, especially Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic Americans, were among the ranching industry’s primary labor force throughout its long history in the American West, particularly in places like Texas.

Racial politics and white supremacy also suffused the community life of Estes Park. Occasionally, events within Estes Park invoked the white supremacy typical of the 1930s and 1940s and residents staged racist entertainment for the amusement of white audiences. The Estes Park Trail covered the presentation of “Dixie Blackbirds,” in 1936. Held to benefit the local volunteer fire department, the Trail promised “a rollicking, frolicking minstrel show” made up of “the leading men of the community, in black face, cavorting around like high school youngsters, making themselves… as ridiculous as possible.” John McGraw was among the men to appear in blackface.[11] Guides to western guest ranches also used the presence of Black staff as a marker of a ranch’s refined service, informing prospective “dudes” that “Some [ranches] have dining pavilions and white-coated colored waiters,” while at less formal ranches, white ranchers and guests dined together as equals.[12] The space between white leisure and Black labor was what defined western luxury.

The types of guests permitted to stay at guest ranches was also up to ranchers’ personal discretion. While few ranches in the West advertised themselves as such, overt racial segregation was common practice on dude ranches in the East. “Restricted” ranches were closed not only to Black Americans, but also to Jews. [13] The Union Pacific’s guide to the West’s dude ranches obliquely referenced this aspect of the “host-guest relationship,” stating: “Most ranches ask for references and investigate them carefully… if not congenial or sociable with other guests they [the undesirable guests] would not enjoy their own vacation, nor would the others.”[14] On western ranches, ranchers “tended to avoid public scrutiny” about their operations as a general rule, but it is likely that they informally practiced some degree of racial and ethnic discrimination.[15]

McGraw Ranch in the Mission 66 Era

Throughout 20th century, the national park acquired guest ranches within its borders, including Irwin Beattie’s Phantom Valley Ranch, the Holzwarths’ Never Summer Ranch, Green Mountain, Onahu, and Sprague’s/Stead’s Ranch, among others. With few exceptions, the park service razed former ranch buildings and structures to return the land to a more natural-looking state. The ideals of Mission 66 guided the park’s efforts. Mission 66 was a federal program that sought to address the environmental impact of rising park visitation and funding shortages following WWII. Along with facilities and infrastructure upgrades, Mission 66 also made funding available for the National Park to purchase and rehabilitate additional privately-held inholdings. [16] In 1966, the park service bought 484 acres of the McGraw Ranch, and the ranch ceased operations as a working ranch. Frank McGraw and his wife, Ruth, sold the ranch in 1973, but continued running the property until they retired in 1979. The national park acquired the remainder of the ranch’s acreage in 1988, and McGraw Ranch narrowly escaped destruction in the early 1990s. When the park threatened to tear it down, Estes Park locals, backed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, advocated for the ranch’s preservation on the basis of the family’s important historic role in developing and supporting the Estes Park community. The National Park Service reconsidered, and McGraw Ranch became a research facility that houses researchers whose work enhances the park’s knowledge and stewardship of its resources.[17]

Conclusion

Today, public interpretation at McGraw Ranch recounts a moment when the park service changed its mind about the stories it wanted to tell at Rocky Mountain National Park. The park’s decision to tell the story of the McGraw family and of dude ranching in the park by preserving the ranch complicated its older, simpler story of the park as an untouched wilderness. Rather than demolishing the ranch, the park service chose to acknowledge the different ways that people existed on and used the land that became the national park. The ranch is also a place that tells the history of race, and the ways it intersects with Colorado’s mountain landscapes, although this part of the ranch’s story has yet to be acknowledged as publicly. In 2020, Coloradans and Americans in general are contemplating racism with the desire to better understand and confront it. Telling the history of race in unexpected places like McGraw Ranch is a reminder that race and racism shaped every facet of American life—especially in the West.

– Ariel Schnee, Public Lands History Center Program Manager

Published 09/02/2020

Sources

[1] Rico, Monica. Nature’s Noblemen: Transatlantic Masculinities and the nineteenth-century American West. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2013. 3-4.

[2] Lears, Jackson, T.J. Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877-1920. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009. 1-11. And Borne, Lawrence R. A Complete History of Dude Ranches. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983, 8

[3] Aaron, Cindy S. Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, 211.

[4] Dude Ranches Out West. Union Pacific Railroad, 3.

[5] “Mountainside Lodge is the Scene of Many Parties,” Estes Park Trail, vol. 7, no. 17, August 5, 1927. And “Music Club Meets with Mrs. McGraw” Estes Park Trail, February 23, 1922. And National Register of Historic Places Form – McGraw Ranch, U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed Jun 24, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/electronic-records/rg-079/NPS_CO/98001163.pdf And The McGraw Ranch Research Centre at Rocky Mountain National Park. The National Trust for Historic Preservation. Denver: The National Trust for Historic Preservation, Mountain/Plains Office, 1999, 17.

[6] The McGraw Ranch Research Centre at Rocky Mountain National Park. The National Trust for Historic Preservation. Denver: The National Trust for Historic Preservation, Mountain/Plains Office, 1999, 3.

[7] National Register of Historic Places Form – McGraw Ranch, U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed Jun 24, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/electronic-records/rg-079/NPS_CO/98001163.pdf

[8] National Register of Historic Places Form – McGraw Ranch, U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed Jun 24, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/electronic-records/rg-079/NPS_CO/98001163.pdf

[9] “McGraw Elected to Office in Dude Ranch Association,” Estes Park Trail, vol. 21, no. 31, November 21, 1941. And “History of Estes Park Rodeo One of Unselfish Devotion,” Estes Park Trail, vol. 18, no. 10, June 25, 1948.

[10] Advertisement. “Carefree Colorado Calls You!” Estes Park Trail, vol. 26, no. 1, August 26, 1946. And Philpott, William. Vacationland: Tourism and the Colorado High Country. Seattle: University of Washington, 2013. 10-11.

[11] “Minstrel Show to be Given Tomorrow Night,” Estes Park Trail, vol. 15, no. 19, August 23, 1935.

[12] Dude Ranches Out West. Union Pacific Overland, 1933, 3.

[13] Rodnitzky, Jerome L. “Recapturing the West: The Dude Ranch in American Life,” Journal of the Southwest, (Summer 1968) vol. 10, no. 2: 121.

[14] Dude Ranches Out West. Union Pacific Overland, 3.

[15] Borne, Lawrence R. A Complete History of Dude Ranches. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983. 2. And Rodnitzky, Jerome L. “Recapturing the West: The Dude Ranch in American Life,” Journal of the Southwest, (Summer 1968) vol. 10, no. 2: 121.

[16] Andrews, Thomas G. Coyote Valley: Deep History in the High Rockies. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015. 193-195, 197, 201.

[17] The McGraw Ranch Research Centre at Rocky Mountain National Park. The National Trust for Historic Preservation. Denver: The National Trust for Historic Preservation, Mountain/Plains Office, 1999, 17. And Sullivan, Kayla C. “Wilderness to Civilization and Back again: An Examination of the Discourses of Wilderness and Historic Preservation in Rocky Mountain National Park.” Order No. 1594511, University of Wyoming, 2015. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy2.library.colostate.edu/docview/1707858096?accountid=10223.