This past winter, a group of friends and I went on a ski-in yurt trip in Northern Colorado. It was a memorable trip for all of us: we toured through fragrant evergreen forests, got sun above treeline, and harvested plenty of snow and smiles. It was also memorable through the decisions we made: each morning we discussed snow conditions, created a travel plan, and, no matter how appealing they looked, avoided slopes that could produce an avalanche. Since Euro-Americans moved west into the Rockies, avalanches have been responsible for numerous deaths, destruction of property, and the closure of transportation routes. The masses of snow, ice, and debris that cascade down mountain slopes are a natural occurrence. However, as the Mountain West’s economy changed over time, they shifted from primarily occupational hazards to primarily recreational ones. Though visitors’ reasons for spending time in the mountains have changed, avalanches have not. The precautions today’s skiers, snowboarders, and other recreationists must take in the backcountry are similar to those taken by fur trappers, miners, and railroad workers traveling in the Rockies centuries before.

Observing how snow behaved during long mountain winters, early industrial workers learned which slopes to avoid, when to be cautious going to work, and how to respond when disaster struck.[1] Early on, people who accessed the mountains in the winter employed smart travel habits (sometimes avoiding the mountains altogether) and depended on their communities to stay safe. Now, long after the decline of the fur trade and silver mining, most avalanche fatalities are recreationists.[2] Despite this shift, the key principles of avoidance, smart travel habits, and community assistance during disasters remain tried and true methods that help limit risk among the backcountry community today.

Avalanche as a Recreational Hazard

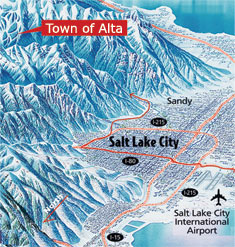

During the 1920s, downhill skiing became popular across the United States.[3] In response to this new type of land use, the U.S. Forest Service began creating “ski areas” on national forest land. If you’re a skier or snowboarder, you probably recognize some of their names: Alta, Brighton, Sun Valley, Arapahoe Basin.[4] These designated areas concentrated recreationists on steep, avalanche-prone terrain. By changing the way visitors viewed this terrain, the Forest Service transformed mountain slopes from places to avoid into a prime skiing locations. This created an avalanche hazard, and it was up to Forest Service snow rangers to find a way to mitigate it.[5]

The Rise of American Avalanche Research

Rhetorically capturing the shift from labor to recreation, early avalanche experts stated that avalanche study in the United States began “for the protection of a winter playground.”[6] The first person assigned to this protective role was C. D. Wadsworth, a snow and avalanche observer based at Alta in Utah’s Wasatch National Forest.[7]

Rangers at Alta observed the causes of avalanches and experimented with mitigation, making the nascent ski resort the birthplace of American avalanche research during the winter of 1937-38.[8] The primary objectives of early avalanche work were to quickly identify and reduce hazards to protect skiers. Observation and research were the next priorities.[9] By the time Americans began consistent research on the topic, Swiss snow scientists had already established ways to protect valuable infrastructure in the mountains. But the focus on recreationists, instead of permanent residents, distinguished the American field from its European counterpart.[10]

This early research culminated into “The Alta Avalanche Studies,” a 1948 initiative to collect all of the information the Forest Service had gathered and “apply that knowledge to the administration of winter sports areas on public land.”[11] This report set the precedent for numerous publications communicating field research to rangers and ski area personnel. These publications included sections on history, snow science, safety, and rescue protocol. Several updated versions of them have been released in this format, with the target audience shifting from Forest Service employees and forecasters to the backcountry community. These texts provided scientific evidence and field experience to show when and where avalanches occurred, how to stay out of their path, and what to do in a worst-case scenario. In relaying this information to a broad community of stakeholders in the backcountry, experts assessed scientifically what nineteenth-century workers learned through trial and error: which slopes repetitively slid, what routes could be travelled safely, and how to help if a friend got buried.

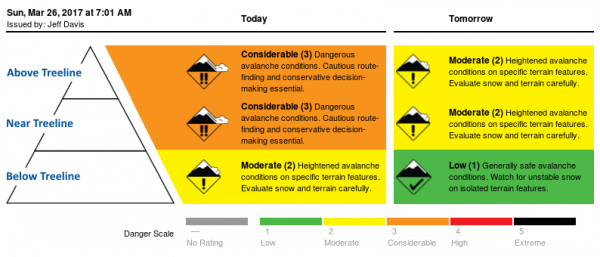

As early resorts became more developed, resort ski patrols began taking over the direct mitigation roles of Forest Service employees.[12] With this, the Forest Service’s avalanche focus shifted to the undeveloped woods and peaks of national forests in response to the growing backcountry ski community. This was done through the establishment of regional forecasting centers in the 1970s and ‘80s. In 1999, this web of forecasters unified under the Forest Service’s National Avalanche Center (NAC), acting as a clearinghouse.[13] The NAC provides backcountry users information about snow conditions and where to expect avalanche hazards. Though allowing backcountry travelers to make their own decisions, this infrastructure is a platform to further spread the tactics of observing, avoiding, and assisting that has saved numerous lives since the arrival of Euro-Americans in avalanche country.

Know Before You Go

As the number of recreationists in the backcountry grows, avalanche forecasters play an integral role in keeping them all safe and informed. Improvements in technology and equipment, such as snowmobiles, lighter skis, splitboards, and Gore-Tex jackets, have allowed recreationists to travel further into the backcountry than ever before. Because of this, avalanche centers have leveraged a framework called “Know Before You Go.” Established by the Utah Avalanche Center, Know Before You Go is “a free avalanche awareness program. Not much science, no warnings to stay out of the mountains, no formulas to memorize.”[14] Site visitors can view informational videos, listen to accounts of avalanche accidents, read easily digestible guidelines on avalanche safety, and find their local avalanche forecasts. Focused solely on informing current and future recreationists about how to remain safe while playing in the snow, this program provides an entry point for those interested in backcountry recreation. Scientific knowledge of avalanches, as well as technology that keeps recreationists safe around them, has changed drastically since the mining days of the old West. However, the traditional tactics of local knowledge (now augmented by avalanche centers and widely accessible information), safe travel, and community assistance are still among the best ways backcountry users can protect themselves in avalanche country.

-Alex Miller, PLHC Research Fellow

Published 04/30/2020

Sources

[1] Early knowledge and attitudes toward avalanches in the Mountain West found in Diana Di Stefano, Encounters in Avalanche Country: A History of Survival in the Mountain West, 1820-1920 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013).

[2] “Statistics and Reporting,” Colorado Avalanche Information Center, last modified 2019, accessed February 27, 2020, https://avalanche.state.co.us/accidents/statistics-and-reporting/.

[3] US Department of Agriculture, US Forest Service, “Ski US: The Evolution of Skiing on the National Forests,” by Montgomery M. Atwater, Alf Engen et al., Brochure (Washington).

[4]Atwater, Engen et al., “Ski US: The Evolution of Skiing on the National Forests,” Michael Childers, Colorado Powder Keg: Ski Resorts and the Environmental Movement (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012), 8.

[5] Definition of “Avalanche Hazard” from US Department of Agriculture, US Forest Service, Avalanche Handbook by Montgomery M. Atwater and Felix C. Koziol, Handbook (1954), 4.

[6] Atwater and Kozoil, Avalanche Handbook (1954), 10.

[7] Ibid, 9.

[8] Ibid, 9.

[9] Ibid, 12.

[10] Ibid, 10.

[11] Ibid, 2.

[12] Greg M. Peters, “From Howitzers to Hotlines,” Your National Forests Magazine (Winter/Spring 2015), Accessed via https://www.nationalforests.org/our-forests/your-national-forests-magazine/from-howitzers-to-hotlines.

[13] Peters, “From Howitzers to Hotlines”.

[14] Homepage, Know Before You Go, 2017, https://kbyg.org/.